Accidental Entomophagy: Eating Bugs!

Resource Details

Written by: Tehreem Chughtai as part of Zoology 507 research (supervisor: Mindi Summers)

Whether you are aware or not, you have consumed insects! We directly and indirectly consume insects, and the practice of eating insects is called entomophagy. Entomophagy is widespread and common throughout the world. While you can find many insect delicacies in Southeast Asia, Africa, Australia, and Mexico, insects are less commonly found on Canadian menus. Canadians are slowly beginning to adopt entomophagy (e.g., cricket granola bars, chips, and salad toppers). If you are hesitant to try entomophagy, it may help to know that we are likely accidentally consuming over 140,000 insect fragments every year through the other foods we eat (FAO 2013). For example, when you take a bite of your favourite mac and cheese, you can find approximately 100 insect fragments (FDA 2018)! The presence of insect and insect fragments in food is both un-avoidable and safe.

Accidental entomophagy refers to the unconscious consumption of insects that have found their way into your food. Insects that are consumed “accidentally” were not reared specifically for consumption but instead found their ways into food storage containers at some point in the complex journey from farm (or factory) to table (Hill 1990).

Why should we be excited about consuming insects (intentionally or accidentally)?

When you have likely already been engaging in (accidental) entomophagy?

Insects can be found in a wide variety of foods in different quantities. Insects can fly into food storage containers during harvest, travel with stored food as it is being shipped or even gnaw into food packaging at the store (Hagstrum et al. 2012). As infestation can occur during food harvest, storage, shipping and manufacturing periods and many times it is difficult to determine exactly when insects entered a food product (Hill 1990). Here are some examples of some foods that can contain insects:

How can we be sure that (accidentally) eating insects is safe?

The foods we eat are carefully regulated to ensure that there are no hazardous levels of insects/other materials. Food inspection agencies set limits for the maximum amount of insect matter (in grams) that can be allowed in a food quantity declared unhazardous for consumption (FDA 2018). Individual insects ending up in food after harvest is therefore normal and non-threatening (Hagstrum et al. 2012). However, stored food items (e.g., cereals, grains) should be discarded if live insects are found, as live insects can carry harmful fungal toxins and bacteria on their exoskeletons (Hagstrum et al. 2012). To learn more about how our foods are kept safe, see Safe Foods for Canadians Act and the FDA Food Defect Levels Handbook.

How can we add more insects into our diets?

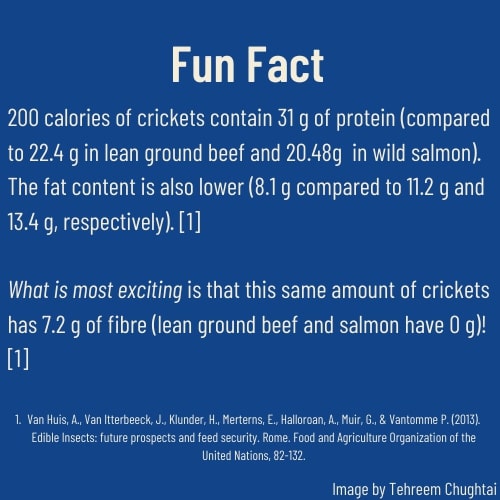

Insect food items are high in proteins, omega 3 fatty acids and fiber (FAO 2013). They are also full of micronutrients like magnesium, calcium, Vitamin B-12, zinc, iron and many more. There are lots of ways to add more insects to your diet. To help you get started, here are a few do’s and don’ts:

Do: Purchase insect product that is produced for human consumption and certified safe by the seller (FAO 2013). When practicing entomophagy, you can purchase pre-packaged insect products on online marketplaces.

Do: Incorporate insects into your regular recipes and get creative! For example, crickets can be roasted and served atop salads or in stuffings and mealworm flour can make soft chocolate cookies!

Do: Talk to your doctor before consuming large quantities of insects, if you have a pre-existing crustacean allergy. When consumed in large amounts insects have the capacity to trigger allergies similar to crustaceans (FAO 2013; Chomchai et al 2020).

Don’t: Eat any live insects found in your pantry or the wild, as they may have fed on harmful bacteria (Hill 1990; Morrison et al. 2019). If you notice live insects in any of your stored foods (cereals or grains), throw away the food and sterilize the containers.

Don’t: Consume insects bought at the pet store as they were not farmed for human consumption.

Recommended reading

Van Huis, A., Van Itterbeeck, J., Klunder, H., Merterns, E., Halloroan, A., Muir, G., & Vantomme P. (2013). Edible Insects: future prospects and feed security. Rome. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 82-132

Food and Drug Organization of the United States. (2018). Food Defects Levels Handbook.

Author biography

Tehreem Chughtai is a Biological Sciences student at the University of Calgary. Tehreem’s areas of interest are stored foodstuff entomology and the role of insects in disease transmission, with emphasis on the Dengue virus. Her interest in pest interactions with stored food products and produce began when finding a Banded Cucumber Beetle in a cucumber in her lunch. Cucumber beetles are not typically found in Canada! This prompted a critical inquiry into the ways pests interact with stored food and produce. A Pakistani born Canadian, as Tehreem gained a greater knowledge of entomology and tropical insects, she began to examine the role of insects as disease vectors. With the dengue virus being of particular concern. Tehreem’s passion within the greater field of biology surrounds public health research, specifically using insects tools to explain the world around us.